Back to School

By Adrianne Murchison

Anticipation and butterflies around the first day of school are not exclusive to students. Parents can be anxious about how the day will unfold, as well.

Before the first day back, parents of children with developmental disabilities have already been tenacious researchers of resources, discovering the best potential outcomes for their child.

The path to high school graduation and employment for children with developmental disabilities starts as early as three years old. Under the federal act that allows Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) for Students With Disabilities, an Individualized Education Program (IEP) is designed for each child. The website, understood.org, will show you how to seek special education services for your child.

An IEP team gathers annually, and sometimes more often, to consider the child’s personal needs and strengths, as well as school curriculum and structure. The team assesses how the student will participate in educational milestones, and the most conducive classroom environment, said Zelphine Smith-Dixon, state director for Special Education Services and Supports with the Georgia Dept of Education.

“Although it’s called an IEP, it’s really about the right services and support for that particular child,” Smith-Dixon said. “Federal guidance requires the roles that are represented. So, the [IEP] team is the parent, a regular education teacher, someone with a grade level curriculum, a special education teacher, and someone who can commit [financial] resources for the district and say, ‘Yes, we can do that.’ ”

With an IEP, students can be in a setting with typical students or solely with classmates who have developmental disabilities.

IEPs are required from age three to 21. At age 22, FAPE is no longer required. However, some school districts can decide if they want to continue to provide FAPE for the balance of the school year after the student reaches 22, Smith-Dixon said.

Parent support can be essential in navigating IEP programs for your child, explains Anne Ladd, a family engagement specialist for the Georgia Parent Mentor Partnership, which helps improve outcomes for students.

“As a family engagement initiative,” Ladd said, “we want to empower and educate families to play a role in decision-making in school and in the community. Regardless of how much knowledge you have when you sit at that IEP meeting, everything changes when it’s your own child.”

Mentors are parents of children with disabilities. They are employed by the Department of Education and work in participating school districts to bring sensitivity to administrators and educators from the perspective of students and their families. This is particularly helpful during district discussions and stakeholder meetings, Ladd said.

“In the beginning of the year, parent mentors can come in to explain to teacher groups why a parent might be angry or under stress,” Ladd said. “Sometimes people are overwhelmed and there is a reason they are behaving badly.”

Mentors also help parents establish positive, lasting communication with teachers. Family engagement is the key to best outcomes for children, according to the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) and the National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability for Youth. Improved confidence, reading and math skills, graduation rates and more successful employment occurred when there was a continuous flow of communication between parents and teachers.

Mentors are matched with families through Parent to Parent, an entity of Georgia’s Parent Training Information Center. They assist parents setting goals and success towards grade levels and graduation, communicate with teachers, keep track of student progress in class, and provide supportive activities.

A Parent’s Journey

Every family has its own set of circumstances that brings complexity to their intended plans, and Jess Goldberg’s clan is no different.

Her sons each have disabilities that require careful thought. Goldberg’s 12-year-old son is on the autism spectrum and will be a student at a middle school in Gwinnett.

Her 11-year-old has an IEP but has not yet been diagnosed with a disability. He completed elementary school last spring and will attend a private school for children with disabilities in the fall.

Goldberg says her younger son has always been an engaged and happy child, but she had a heightened awareness of his subtle behavior as a result of her older son’s diagnosis. A county evaluation of the younger son at age two showed he was not exactly where he needed to be.

“There was this X factor,” Goldberg recalled. “He was struggling emotionally and also with focus and executive functioning.

I think they eventually gave him an IEP just on my persistence. The team would consult with his teachers. Every year things got a little more challenging for him.”

Goldberg and her husband have college goals for their boys and are already contemplating what dormitory life would look like. The Gwinnett mom is a fierce protector of her sons, but also a realist with their educational needs.

“The IEP meeting is very formal and a legally binding document,” Goldberg said. “It’s intense and can be intimidating. I try to go in with an open mind and know I am there for one reason – to make sure my kid is getting everything he needs to be successful. It’s a big negotiation. But I have found there are a lot of wonderful resources in Gwinnett.”

From Goldberg’s perspective, each person on the IEP team, which she meets with a few times a year, has his or her own objective, and some will inevitably conflict. Her greatest concern, beyond grades, is whether her boys understand the tasks that help them manage daily life.

In lower grades, her older son was in an autism level three program that required substantial support. He progressed to level four by sixth grade and has been able to attend classes with students without disabilities. The classes allowed for support staff, if necessary, to escort her son out of the classroom for a brief change of atmosphere.

However, the Goldbergs accomplished this by transferring their son to another public school district for the sixth grade only. He returns to his home district this year.

“Our district didn’t offer that [service],” Goldberg said. “I’ve always wanted him in a general education setting as early as he could handle it. He has had some co-classes with general education and special education teachers.

He doesn’t want to be known as a kid with autism. He wants to play basketball in middle school and be known as the tall kid who loves basketball. And then, he wants to go to Norcross High School.”

Community Resources

Goldberg has accessed many community resources, such as Parent to Parent, to find the right answers for her sons’ educational paths.

Among them, the Blonder Family Department for Special Needs at the Marcus Jewish Community Center of Atlanta supports families with IEP recommendations, public school resources and parent networking.

“We work with DeKalb County,” said director Jennifer Lieb. “But some parents choose private school, and we help them navigate that.”

A significant part of Blonder also guides parents seeking an early diagnosis of a disability for their infant or toddler.

“Until you are in a place of needing support, you are not going to look for those services,” Lieb said. “Parents might see that their children are not reaching certain milestones, and they get nervous. We help guide them to what steps they can take if they need support.”

Such resources include Babies Can’t Wait, a program with the Georgia Department of Public Health, where professionals assess a child’s present level of development from birth to age three. If a child is eligible, Babies Can’t Wait will connect families with community resources and develop a service plan that includes desired goals for the child.

Project SEARCH

With supportive resources, from Pre-K through secondary education, children with developmental disabilities can graduate from high school feeling independent and empowered with fulfilling employment.

Project SEARCH has been especially successful in its high school-to-work transition program for children with developmental disabilities. Students who have finished high school credits but have not completed their IEP, work as interns at Project SEARCH sites, such as hospitals.

Project SEARCH interns at North Fulton Hospital

Project SEARCH interns at North Fulton Hospital

Internships can last up to 10 weeks. Part of the goal is to become permanently employed, said Bonnie Seery, the Project SEARCH coordinator for Georgia. “Usually, there are specific jobs that students want or are interested in. With the internships, they can see what their own talents are,” she said.

Will Crain of Gainesville worked three 10-week hospital rotations through Project SEARCH. He worked in the mailroom, helped mud walls, paint and more. “Will is one of those kids who wants to work,” his father Scott said. “He is so excited about the possibilities.”

After working a Project SEARCH position in the cafeteria at Lanier College and Career Academy, Will secured permanent employment.

“He is a joy,” his supervisor Kellie Hoffman said. “I love coming in and knowing he will be there. I just love him. He makes my day better. He is just an awesome person.”

Hoffman gives Will a list of duties each day such as sorting, clearing and cleaning that he works through expeditiously, she said. “He would try to beat his time every day. First it took about an hour. Now, it’s down to 23 minutes.”

Project SEARCH was started in Cincinnati Children’s Medical Center in 1996. The goal was to hire and train people with developmental disabilities to fill entry-level positions in the emergency department.

Georgia has been successful in placing interns at each of its nine sites, mostly hospitals including Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and Emory University Hospital Midtown Atlanta. Total Systems Services, a credit card service company in Columbus, GA, also serves as a site.

“Some of what I see – and it still gives me goosebumps – is [interns] come in apprehensive and scared, and by the middle of the year, you just see their confidence change dramatically,” Seery said. “Students know their way around the entire hospital [Archbold Medical Center in Thomasville, GA]. They speak to everyone and know them by name. It’s such growth.”

Interns organize files, order supplies, greet and escort patients to waiting areas, clean spaces and more.

College and Career Goal Planning

As early as age 14, parents can contact the Georgia Vocational Rehabilitation Agency (GVRA) to start planning for their child’s college life or professional career.

“We start working with children with disabilities early,” said Robin Folsom, GVRA director of communications and marketing. “We work with people of all disabilities and believe everyone who wants to work should have a right to work. It’s our job to make that happen.”

Counselors guide children in identifying goals for college or careers, then coordinate with schools to establish a plan of support. Every plan is individualized with varying details such as training or devices to assist in hearing or seeing.

Other helpful resources for services and supports are the Georgia Department of Labor or Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities.

Higher Learning

Some local colleges and universities offer higher education for students with disabilities, who would not meet typical enrollment requirements, through the Georgia Inclusive Postsecondary Education Consortium (GAIPSEC). The consortium is located at the Center for Leadership in Disability (CLD) at Georgia State University (GSU).

In 2015, the CLD within the School of Public Health at GSU received a $2.5 million, five-year grant for the consortium’s Inclusive Postsecondary Education (IPSE) Programs for Students with Intellectual Disabilities. The university has been meeting quarterly with state agencies and other stakeholders since 2012, said Susanna Miller-Raines, coordinator of the consortium and grant.

“There is a leadership team,” said Miller-Raines. “Members are interested stakeholders who want to be part of this movement. We have trainings for parents, school districts, colleges and universities to help them learn to prepare students for postsecondary education.”

The growing list of participants includes Kennesaw State University’s Academy for Inclusive Learning and Social Growth. In this two-year program, students audit courses and study to earn a Certificate of Social Growth and Development.

Admission requirements for Kennesaw State’s non-accredited programs include a third-grade reading level, basic math abilities and skills sets that are cultivated through successful, goal-oriented IEPs.

In East Georgia State College’s CHOICE Program for Inclusive Learning, students audit academic classes on a schedule that is tailored for them. They have opportunities for job shadowing and internships.

Like Kennesaw State, students at East Georgia receive a certificate upon completion of the program. “Inclusive college programs prepare [students] for adult life,” Miller-Raines said.

Though the journey of a child from birth to adulthood can seem daunting for any parent, there is support for children with disabilities the entire way. Babies Can’t Wait, IEPs, vocational rehabilitation and postsecondary education are some of the major guideposts.

“I tell parents, always remember teachers and administrators want the best for your child,” Goldberg says. “Also find a network of parents for support. Find your tribe, your village, through your church, synagogue or social media. That’s how you learn about options.”

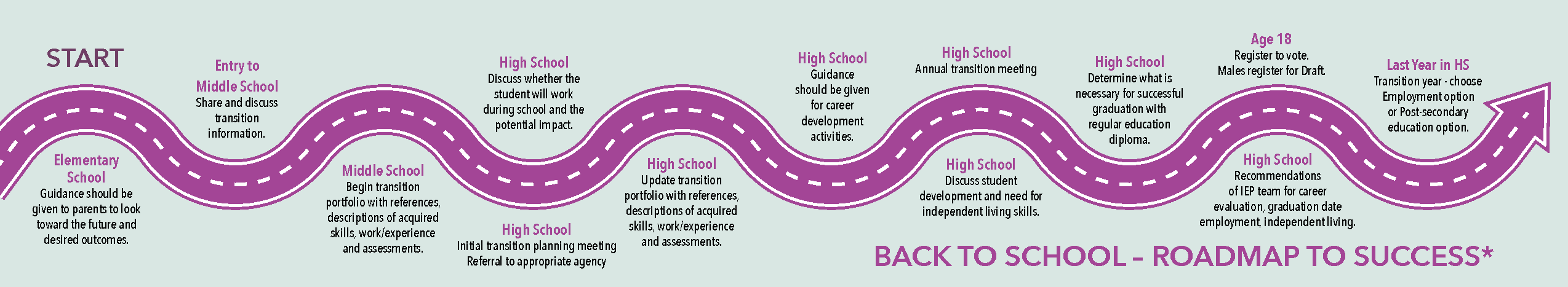

Back to School – Roadmap to Success*

Start

- Elementary School: Guidance should be given to parents to look toward the future and desired outcomes.

- Entry to Middle School: Share and discuss transition information.

- Middle School: Begin transition portfolio with references, descriptions of acquired skills, work/experience and assessments.

- High School

- Discuss whether the student will work during school and the potential impact.

- Initial transition planning meeting Referral to appropriate agency

- Update transition portfolio with references, descriptions of acquired skills, work/experience and assessments.

- Guidance should be given for career development activities.

- Annual transition meeting

- Discuss student development and need for independent living skills.

- Determine what is necessary for successful graduation with regular education diploma.

- Recommendations of IEP team for career evaluation, graduation date, employment, independent living.

- Age 18: Register to vote. Males register for Draft.

- Last Year in HS: Transition year - choose Employment option or Post-secondary education option.

*Download the roadmap graphic here.

To read more in Making a Difference magazine, see below:

Tags: Advocacy, Making a Difference